-

D-Day 80 Commemorations

A wonderful afternoon was enjoyed by around 150 Members and guests attending the D-Day80 Lunch, held in the Carisbrooke Hall at the VSC on 6th June 2024.

The atmosphere was amazing, with guest sharing stories and memories at this special, commemorative event.

Many thanks to our guest speaker, VSC Member and retired Police Inspector, John Henri Gilbert, who provided a fitting tribute on the day. John is the son of a French-Canadian tank gunner of the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade. From his home in Devon, he now writes about Canada’s participation in ‘Operation Overlord.’ His specialist topic is the fierce and often brutal fighting to liberate Caen (a city, Hitler and his Normandy Legions refused to abandon), which was Field Marshal Montgomery’s D-Day objective.

Music was provided by guest vocalist, the talented Adam Christopher Rhys. Adam covered much-loved favourites from Bing Crosby to Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra.

In addition, The Polka Dots performed as part of the entertainment! With classic songs from legends such as Glenn Miller and the Andrews Sisters as well as cheeky retro twists on modern numbers from the likes of Dolly Parton and Whitney Houston. They certainly had many guests singing along, and a few on their feet!

Here are a selection of images from this special event at the VSC.

As dawn broke on the 6th June 1944, the world held its breath. The largest seaborne invasion in history was about to unfold along the Normandy coast of France, marking a pivotal moment in World War II.

This year, approaching the 80th anniversary of D-Day, we are reminded of the monumental scale and profound significance of this event. The combined British, US and Canadian military operation was a testament to human courage, resilience and the relentless pursuit of freedom against tyranny.

VSC members were invited to share their family stories, and we are thrilled by the response. Please find their stories below, which can be expanded by clicking on the ‘+‘ by each name.

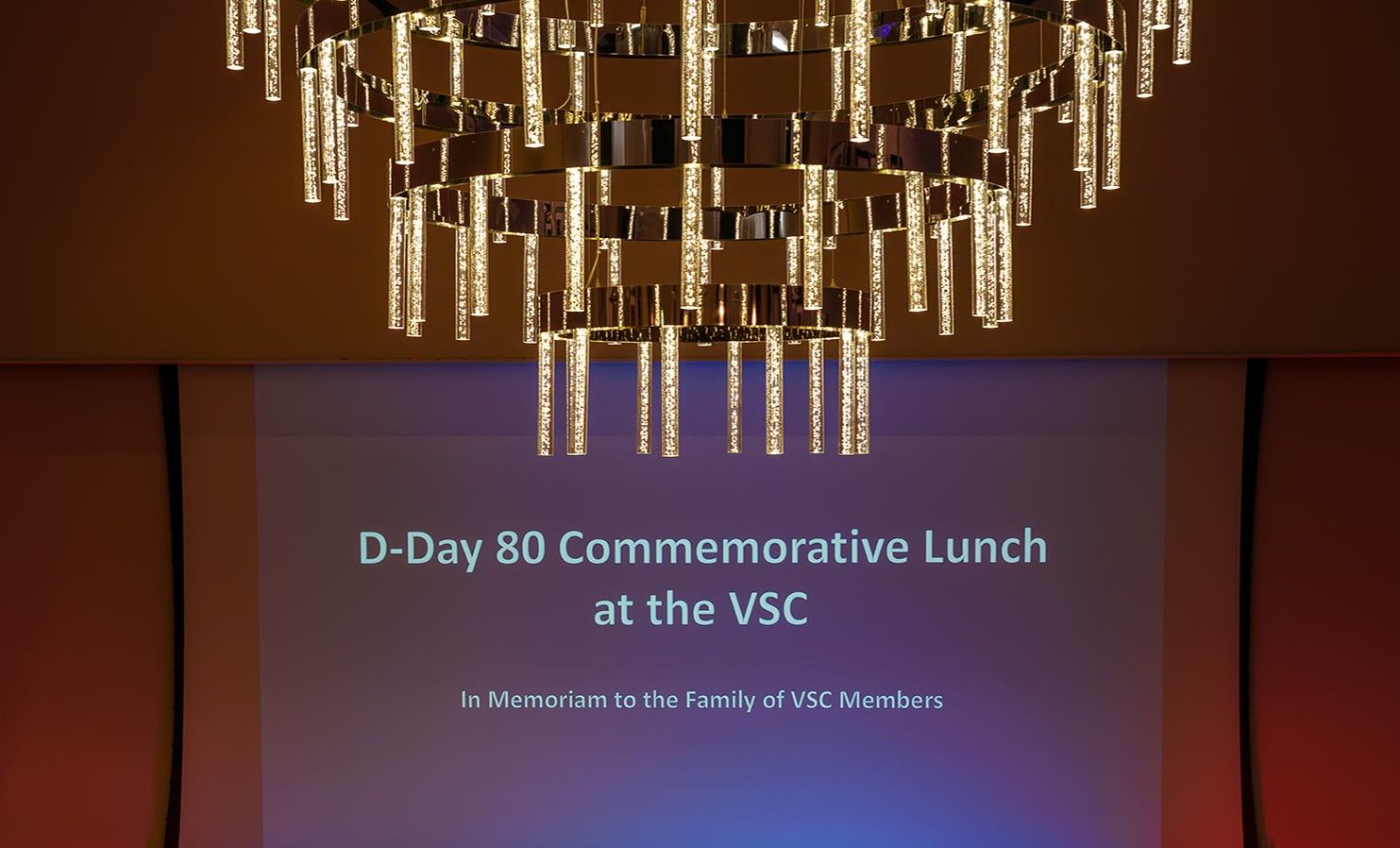

‘The Weekly Warbler’ makes an interesting read. It is the D-Day edition (12th June 1944) from HMS Waveney, provided by VSC Member, Peter Benning, whose late father, Corporal Dominic Benning, was onboard and landed as part of a combined operations assault – he was Royal Corps of Signals and landed with Canadian troops. To access the content, simply click on the image below.

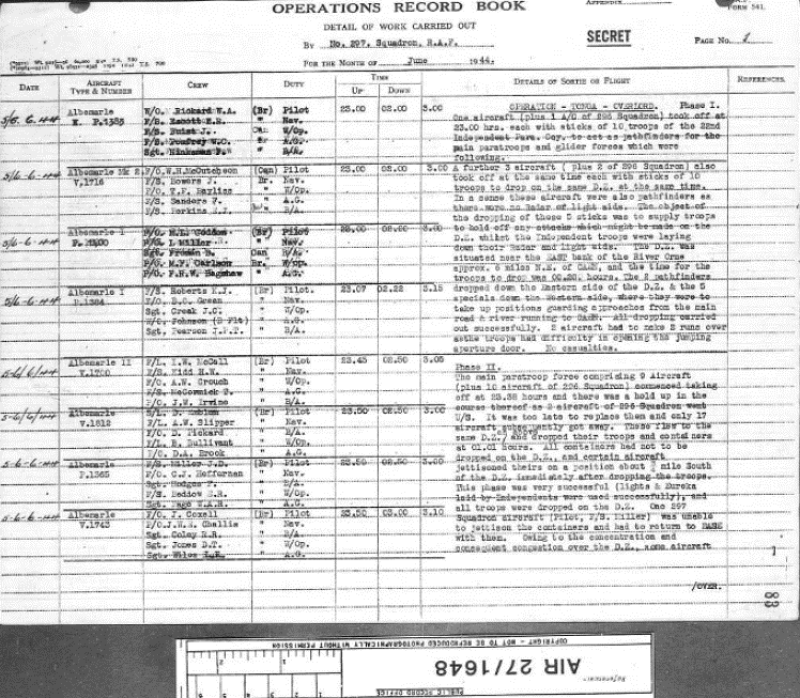

Flight Sergeant Eric Ronald Escott, RAF 297 Squadron

Trevor R. Escott’s father, Flight Sergeant Eric Ronald Escott, was air navigator of the first aircraft to take part in Operation ‘OVERLORD’. Here is his story.

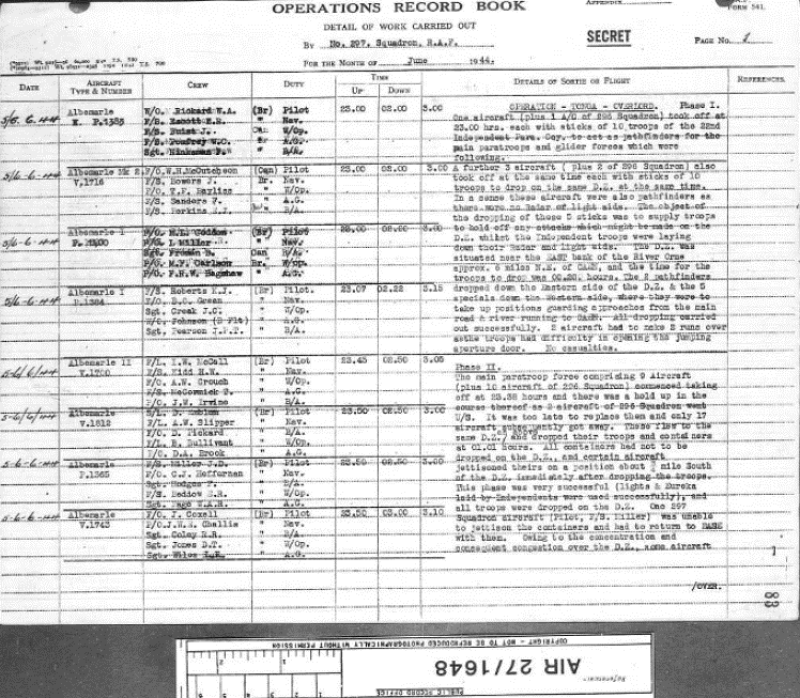

On the night before the D-Day landings, the very first aircraft of 297 Squadron to take part in Operation ‘OVERLORD’, an Armstrong Whitworth Albemarle MkII, aircraft number P.1383, took off from RAF Brize Norton at 23:00 hours. This marked the beginning of Operation Tonga, Phase I – the air navigator of this first aircraft was my father, Flight Sergeant Eric Ronald Escott, then aged 32.

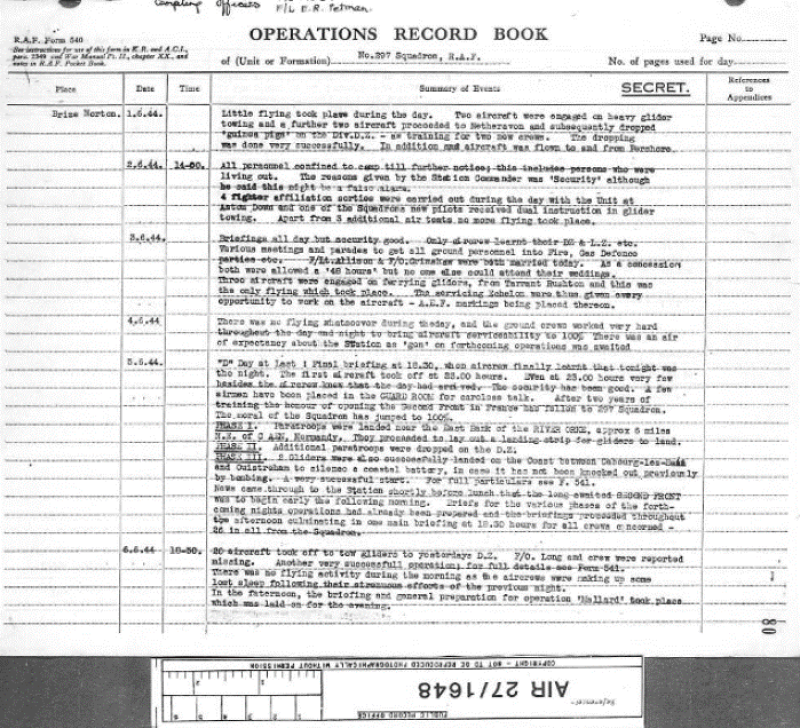

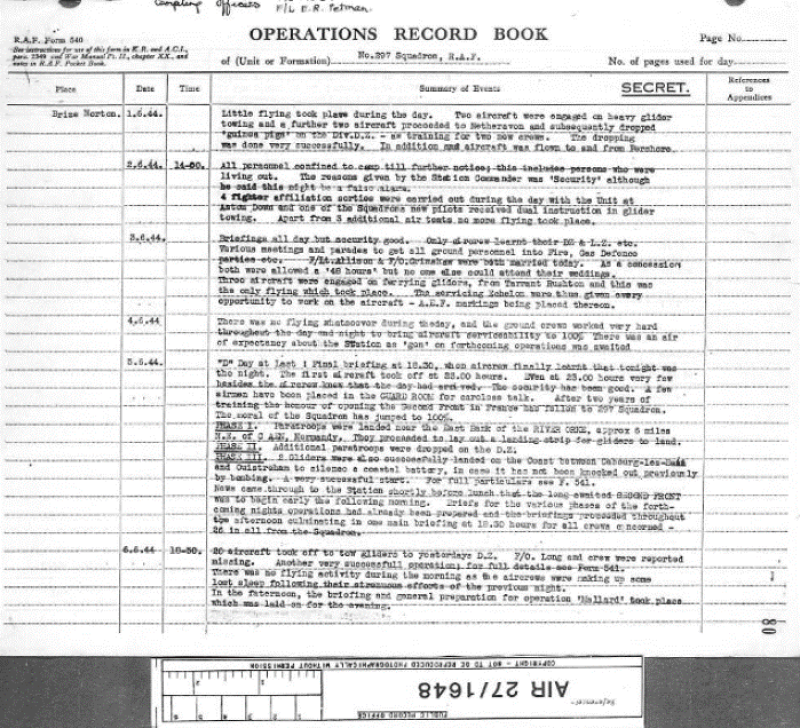

An extract from the RAF Operations Record Book for 297 Squadron reads: ‘“D-Day” at last. Final briefing at 18.30, when aircrew finally learnt that tonight was the night. The first aircraft took off at 23.00 hours. Even at 23.00 hours very few besides the aircrew knew that the day had arrived. The security has been good. A few airmen have been placed in the GUARD ROOM for careless talk. After two years of training the honour of opening the Second Front in France has fallen to 297 Squadron. The moral of the Squadron has jumped to 100%.’

A second Albemarle, from 296 Squadron, took off at the same time. Each aircraft was carrying a stick of 10 troops from the 22nd Independent Parachute Squadron whose mission was to act as pathfinders and lay out a landing strip for gliders using specialist devices which transmitted location information. Immediately after these first 2 Albemarle’s took off, a further 5 followed, 3 from 297 Squadron and 2 from 296 Squadron, each aircraft also carrying a stick of 10 paratroops. The drop zone for this mission was near the east bank of the River Orne, approximately 6 miles north-east of CAEN and the pathfinders dropped down the eastern side of the DZ, with the 5 specials dropping down the western side where they were to take up positions guarding approaches from the main road and river running to CAEN.

Having taken off at 23.00 hours, my father’s Albemarle crossed the ‘enemy’ coast at 00.18 hours at an altitude of 1,180 feet. The paratroops were successfully dropped at 00.23 hours at an altitude of 550 feet. The Albermarle then returned to base, crossing the ‘enemy’ coast at 00.43 hours at an altitude of 6,000 feet and landing at Brize Norton at 02.00 hours.

My father very rarely ever spoke about his wartime experiences, something I believe was often the case for many veterans. He only ever mentioned Operation Tonga to me once, just telling me that they had dropped special forces personnel in France, immediately proceeding the D-Day landings, and that these special forces personnel took special devices with them which they would position on the ground and which transmitted location information for the paratroop and glider forces that would follow shortly later, helping them to land in the correct location (of course, all of these missions took place during nighttime hours). My father also told me that during his service with 297 Squadron, most of their missions were to drop agents and various supplies to French resistance fighters and, after D-Day, also to drop French troops. Crossing the English Channel, and to avoid detection by enemy radar, they often flew at such low altitude that they left a wake in the water.

Researching into my family history, and wanting to understand more about my father’s wartime experiences, and I was able to accomplish this by searching through the outstanding range of military records that are held by the National Archives.

Click here to view a PDF of the RAF Operations Record Book shown below.

Major Albert (Bert) William Mitchell Ld’H, 6th North Staffs Regiment

John Edwards OBE shares the story of his father-in-law, Major Albert (Bert) William Mitchell Lt’H.

Albert William Mitchell was born on 20 November 1923 at home, Bowey Road, Stoke on Trent to Joseph and Nellie and he was their only child. His father won the Military Medal in WW1 for carrying his injured commanding officer off the battlefield. An example of bravery that Albert was also to show in WW2 years later.

Albert was schooled at St Joseph’s College, and he studied hard. He was taught how to play the piano by his aunt Ivy but would rather play football and cricket. He was taken to Stoke City matches as a child by his father, and to cricket by his Uncle Percy; he had 2 uncles and 2 aunties who all looked after young Albert.

On leaving school he went to the Clearing Bank, which by then had relocated to Trentham Gardens due to WW2. Albert was subsequently called up and was commissioned into the 6th North Staffs Regiment (his father served in the 5th North Staffs). He landed on JUNO beach a few days after D-Day. He disembarked the landing craft going over the side using the netting holding a bicycle as well as all his kit and equipment. Going over the side and into the sea was quite a feat for a man who could not swim and never ever learnt to swim.

On reaching the beach, he got his platoon together and they then cycled off in the direction of Caen. On 8th July, in the Battle for Caen, he was blown up by a mortar round and was casevaced. Most of his platoon are buried in the Cambes-en-Plaine cemetery. He was able to take the family to a field near here, and he showed us where the fighting took place, the trenches and where he was wounded. (Interestingly the medic who carried him to the dressing station, “Doc” as he was nicknamed, met Albert by chance in Hanley some 40 years later).

He returned to the UK, Queen Elizabeth hospital, Birmingham for treatment and was then sent to the North Staffs hospital to convalesce and also to be nearer to his family. He was nursed back to health by a Red Cross volunteer, Eunice Machell, who obviously did a fantastic job because later he married her. The shrapnel remains in his body to this day, and it often caused a fuss going through the scanner at airports.

When he was fit and able, he was sent to Northern Ireland to be the Commandant of a German POW camp. He was then posted to Bury St Edmunds to be the Commandant of a larger POW camp of 3000 prisoners, and this is where he ended the war. Years later he was still in touch with some of the men, who were now back in Germany.

He married Eunice in 1952 and they settled in Tittensor, Stoke on Trent. Rosemary, their only child, was born in 1957. Having a good head for figures, he trained as an accountant and did his articles in Hanley. He then had his own accountancy business from 1963. He never really retired but left Birch Terrace, Hanley in 1988 to work from home.

Never forgetting his time in the Army, he would visit his fallen comrades in Normandy annually and became a member of “The Friends of Thury-Harcourt”, a town in Normandy the 6th North Staffs helped liberate as a part of the efforts by the 59th Division. He stopped travelling when his passport expired but daughter, Rosemary and son in law, John are now members, and have returned in the past and will do so in the future. They will be in Normandy this June to celebrate the 80th Anniversary.

Albert was a member of several veteran branches, taking roles on various committees. He had a particular relationship and fondness with Newcastle High School and the Normandy Trust, and he would accompany the school on trips to Normandy and tell the pupils of his experiences. In 2004, the 60th Anniversary of D-Day, he was awarded France’s highest military honour, the Legion of Honour, by the French Ambassador in London.

Bert died of COVID (and old age) on 15th April 2020. He was a devoted husband to Eunice, who sadly died in 2010, a fantastic father and father-in-law to Rosemary and John, and a fun grandad to Charlotte. Bert was a family man, a Stoke City fan, a man who cared, a man who inspired, and a gentleman, who led, and had, a full life. His great-grandsons, Nathaniel, aged 5 years and Solly aged 15 months, will be told of his exploits, and will, in time, become members of “The Friends of Thury-Harcourt”. He will be missed, but he will never be forgotten, for we will remember.

Major Albert (Bert) William Mitchell Ld’H was featured in the following news articles:

STOKE-ON-TRENT LIVE: War hero who cycled from the beaches of Normandy dies aged 96

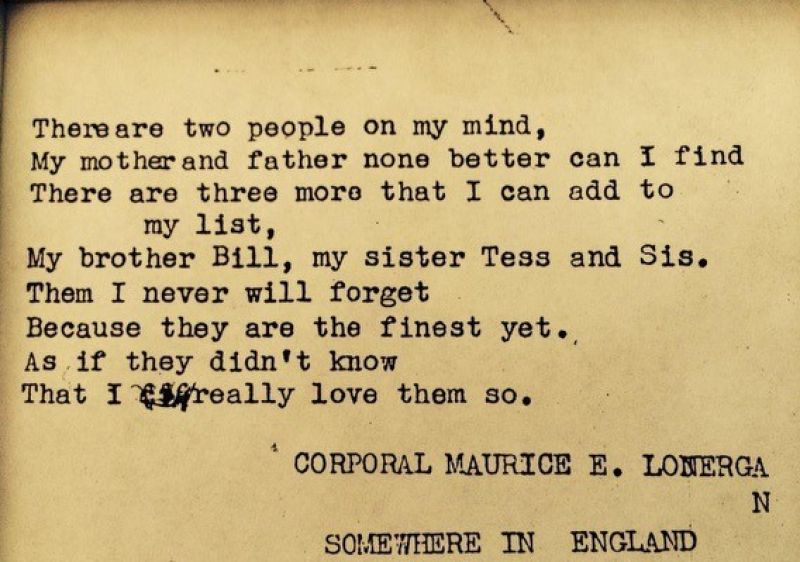

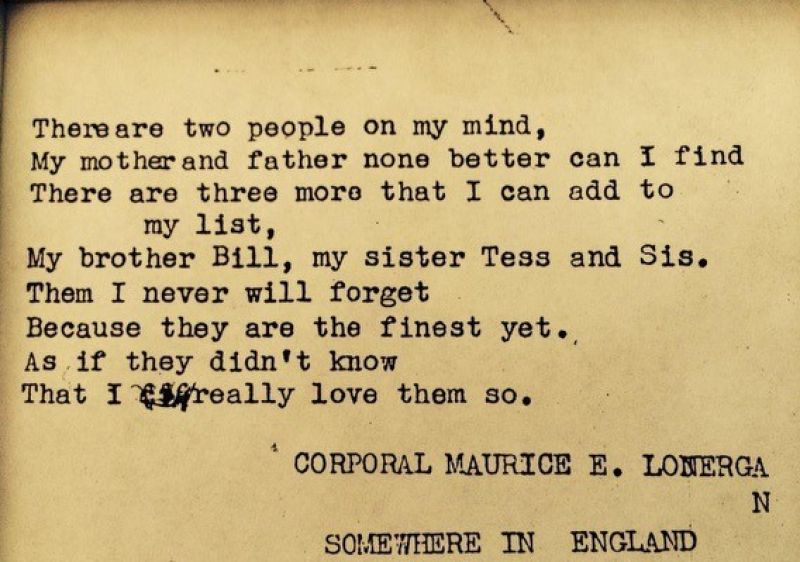

Corporal Maurice E. Lonergan

This poignant poem was submitted by William Lonergan, whose Uncle Maurice Lonergan wrote it prior to boarding a troop ship bound for Omaha Beach. He survived the war, married, and had two children.

Lt (j.g.) Howard W. Rhodes, Jr., USNR

The massive invasion fleet of 5,000+ vessels that sortied from English ports for Operation NEPTUNE in June 1944 included a little-remembered class of gunfire support ships designated LCFs (Landing Craft Flak).

The LCFs were conversions from the versatile Royal Navy Landing Craft Tank (LCT) platform to provide close-in AA support for the troops landing on the beach. The LCTs were modified by welding shut the bow ramp and installing a steel deck over the open well for the gun mounts, creating below-deck space for officers’ country, crew berthing, messing, magazines and stores.

The LCFs were 195.8 ft LOA with 21 ft beam and light displacement of 440 tons. Their armament consisted of four 40mm pop-poms and eight 20-mm machine guns. The complement included four officers and about 60 enlisted men, the majority of whom were gunners. The Royal Navy transferred 11 of the LCFs to the U.S. Navy for the D-Day assault. One of them, LCF18, was commanded by Lt (j.g.) Howard W. Rhodes, Jr., USNR. He was my father.

He was one of the many thousands of young men who left their civilian careers to join the navy in 1942. They were rushed through an abbreviated midshipman indoctrination course in the United States – typically two or three months — before shipping out to Britain.

Old Salts derisively called these young reserve officers “Ninety Day Wonders.” Howard Rhodes and his crew were transported on the Queen Elizabeth from New York City to Rosneath in December 1943. The Royal Navy LCFs were recommissioned into the U.S. Navy in March, and they sailed down the West Coast to Falmouth, where the U.S. Navy had set up an amphibious warfare training center. They participated in Exercise Tiger at Slapton Sands. As D-Day grew near, they shifted to Salcombe.

Due to the obsessive concerns for secrecy, the commanding officers of the ships in Salcombe did not receive their orders until several days before the sortie date. When Lt (j.g.) Rhodes left the briefing hall carrying his copy of the operation orders and intelligence documents, a pair of armed U.S. Marines escorted him back to his ship. “Are you here to protect me?” he asked. “No sir,” they replied, “We’re here to shoot you.”

He had only a few days to study and digest this four-inch stack of paperwork before D-Day. The four US LCFs sortied from Salcombe in the late afternoon of June 3 and joined with vessels from other ports to form a 120-ship convoy designated U-2A. Their target was Utah Beach.

Every one of the ships in U2-A was commanded by a Ninety Day Wonder. Because the convoy included a large number of open-well LCMs (usually referred to as “mike boats”), their transit speed was limited to five knots. The weather worsened during the night to the point that SHAEF headquarters decided to delay the invasion date by 24 hours. Messages went out to the ships in the invasion ports. Unfortunately, the ships in Convoy U-2A failed to receive the radio signal and continued to plough ahead through heavy seas and near-zero visibility during the night. Station-keeping aboard the flat-hull keel-less ships was a nightmare, and collisions were frequent. The ships steaming in a single-file two-column formation showed no running lights other than a weak blue stern light. They were nearly halfway across the channel when they got the notification on the morning of June 5. They turned around and steamed most of the day northward to Portland harbor, where they refueled, and sortied out again at about 0200. The weather was not much better, but they arrived at the designated rendezvous point off Utah Beach just before dawn of June 6. The commanding officers had been on their open bridges continuously for 70+ hours.

But there would be no rest. The ships immediately moved to take up their positions for the assault. The four LCFs, streaming minesweeping gear, led the first wave of landing craft into Utah Beach. One of them, LCF 31, spectacularly exploded a bottom mine and sank almost immediately. It was just the first of the many ships and craft that were sunk by underwater mines off Utah Beach that day. With vessels blowing up all around them, the three remaining LCFs maneuvered to provide close-in gunfire support with their heavy machine guns on the flanks firing at targets-of-opportunity ashore, but their primary mission of AA protection was rendered unnecessary by the total dominance of the skies by Allied air power.

As the invasion moved inland over the following days, the LCFs became part of the nightly screening force to protect the northern flank from German high-speed e boats operating out of Cherbourg. Two weeks later, a massive northeasterly gale swept across the exposed anchorages, wreaking unimaginable damage to the ships on the lee shore. When the wind finally abated, there were more than 2,400 ships and craft wrecked on the beaches. One of them was US LCF 18, whose anchor lines had parted.

Attempts to refloat the ship were futile until the next spring tide on July 5, when an LST towed the ship off. They returned to England, and the ship was turned back over to the Royal Navy at the end of August. The officers and men were shipped back to the United States for reassignment.

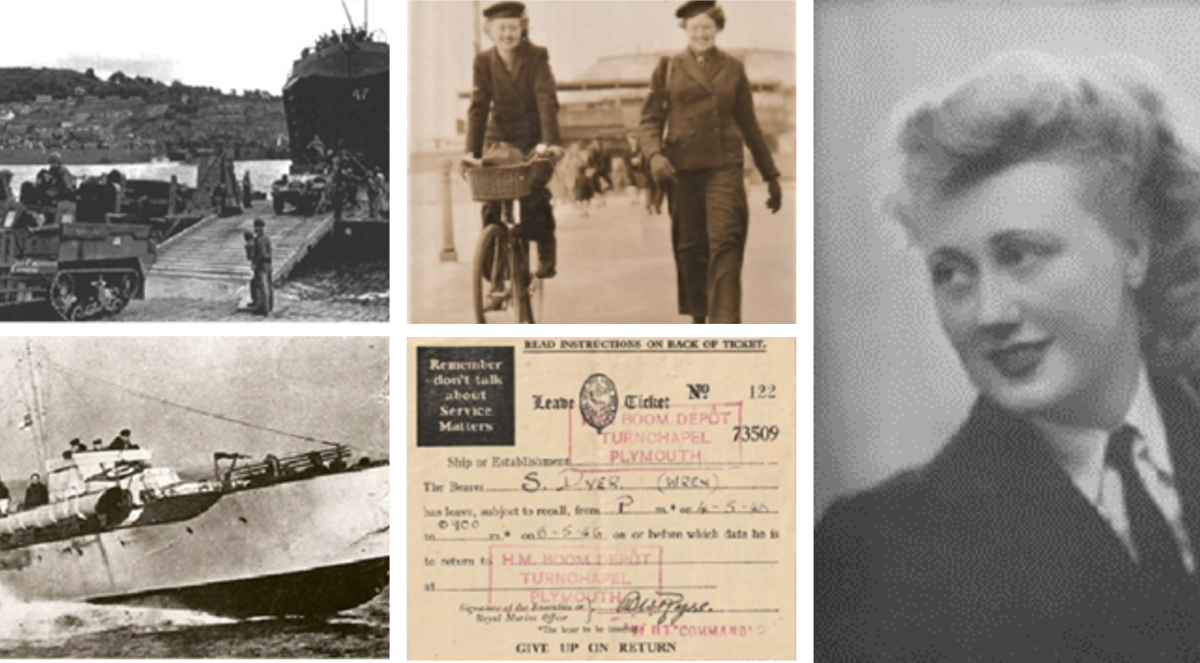

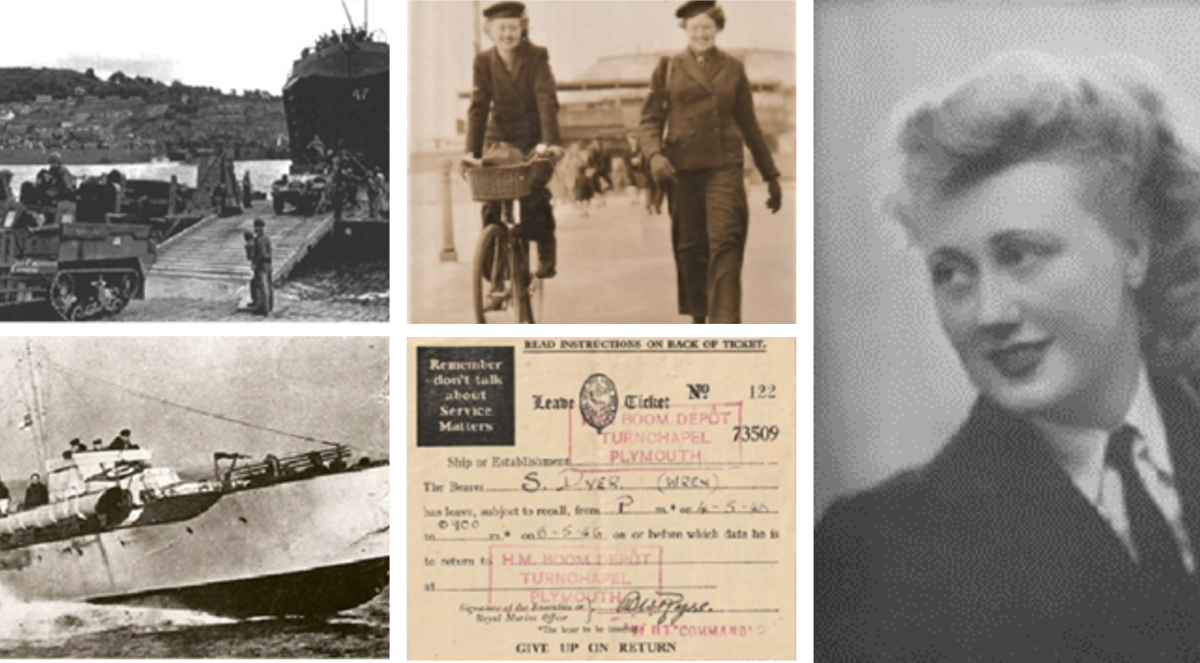

Shirley Burr, WRNS QO 29087

Click here to read the full story of Shirley Burr’s – “My Life in the WRNS 1943-1946”

The Americans came as preparations started for D-Day. As the build up continued, Shirley and the other Wrens were hard at work. She mentions the number of Americans “… one can’t walk across the deck of the Belfort now without being whistled and shouted at from the Yankee Barges that are anchored in midstream – and Dartmouth is lousy with them – and there have been more muscles than that round here.”

“Went to a dance at the Guildhall, Dartmouth last night, Thousands of Yanks – so came back chewing frantically and my pockets stuffed with candy etc – a Yankee barge nearly collided with the ferry on the way back and for a few moments had visions of us swimming for it…”

Of course we were leading up to D-Day although we did not appreciate that at the time. All leave was stopped from March 1944; letters and telephone calls were heavily censored. Two other girls and I were friendly with the officers on board one of the big LCTs. We had often been on board for dinner where white bread and other goodies were served by a black steward wearing white gloves. Orders had come through that no one was allowed on any of the vessels in the harbour unless on duty. But we had had an invitation one night and were determined to go. So we shinned up the side of the vessel with me wearing my friend’s coat and cap whilst he came up behind me to hide my legs from the Guard House opposite. We had a lovely evening and then came home. At about 2am there were footsteps and male voices in the hall outside the cabin belonging to the two other girls who were then carted off by the Military Police. I waited in fear and trepidation but nobody came for me! The following morning the CO informed us that these two girls would be kept in solitary confinement. I was trying to look inconspicuous at the back of the room but soon realised that they had gone into the cabins of their officer boyfriends where the Top Secret charts and Documents were laid out after being delivered that day. Luckily I had not gone!

Of course D-Day itself was postponed because of foul weather. I remember those poor chaps loading into the Landing Craft with their equipment, tanks and armoured vehicles and having to wait another 36 hours before they could finally move. What must their feelings have been? Many of them I had met and talked to or rather they talked. They wanted to show us pictures of their wives and girlfriends – a sympathetic ear and talk to hide their fears.

When D-Day arrived (8 June 1944), the horizon was black with ships. I woke all our quarters and made them look from our windows at history in the making. Our big LCT did not go until a day later and evidently went and liberated Guernsey. Nearly 500 craft sailed from Dartmouth, but of course our Coastal Forces had done their job. Our boom defence across the mouth of the river was now no longer needed and was duly blown up. We had fish for days after!

John William Worthington, Royal Marines Commando

Mark Worthington writes of his late Grandfather’s part in the D-Day landings. His grandson remembers him as a modest man, who deserves to be remembered for his bravery, sense of humour & kindness.

“He never really talked about it until the 75th Anniversary, when he was invited to attend the memorial events in France & Portsmouth. Together, we returned to Juno beach along with several other veterans – it was the beach he had landed on during D-Day. We took part in memorial services in both France and Portsmouth. This was a special time for my Grandfather and for myself.”

Sadly, John William Worthington passed away on 19th October 2021 – his ashes are buried along with the small pot of sand he collected when he and his grandson visited Juno beach. John always said the real hero’s were the young men that lost their lives as they left the landing craft that day. As far as he was aware he was the only one from his landing craft that survived D-Day.

The following are extracts from newspaper articles written at the time of D-Day 75, followed by some photographs of Mark and his Grandfather in France, including their visit to the Bayeux War Cemetery and Memorial in Normandy.

SYDNEY MORNING HERALD (Australia)

John Worthington, 94, was given the job of “clearance” on that day. “On the way in we hit a couple of mines, blew the front off our craft. Then we hit the beach.”Juno Beach. “There were loads of mines everywhere. We were stabbing our bayonets in the sand, there was a shortage of mine detectors.” The next day he was assigned to the padre, taking the ID badges from those killed in the minefield. He remembers the reverend strolling ahead of him as if without a care. “I thought ‘I’ll walk in his footsteps’. We came out all right.” Later, he served in the Far East, landing at Rangoon.“It seems a long while ago really,” says the man who spent much of the rest of his life as a lobster fisherman in Norfolk. He thought he’d come to the event “Because I probably won’t go again. I’m nearly 95. Chances are.”

Read the full Sydney Morning Post news article here.

THE DAILY MAIL

John Worthington, 94, landed on Juno beach at dawn on D-Day, survived when his craft was struck by a mine, and was given the perilous job of mine-detecting to clear a path for the Army – by (very carefully) sticking a bayonet into the sand. Yesterday he said: ‘As far as I know all my comrades were killed who were on the same landing craft. It got to the beach, the other chaps went up the beach but I don’t know what happened to them. An officer told me to transfer to other duties. I was the lucky one. ‘I had to search for mines. You pushed a bayonet in the sand at an angle and had to hope you didn’t hit the detonator.’

Read the full Daily Mail news article here.

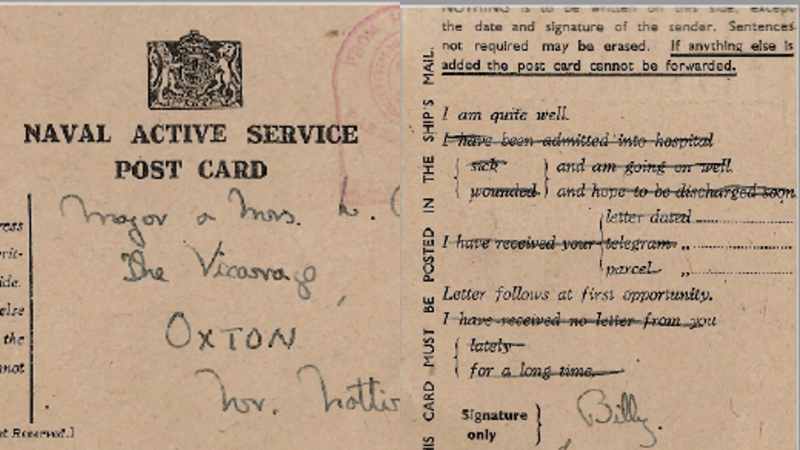

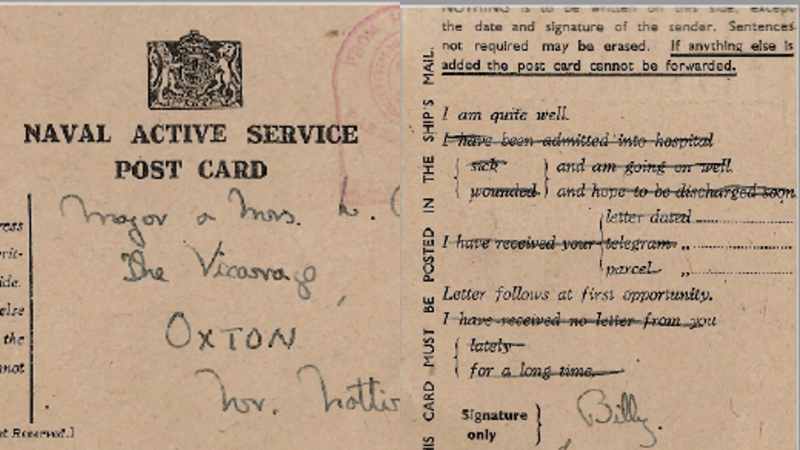

Lieutenant William Ackroyd, Royal Marines

At the time of D-Day, Charles Ackroyd’s father, William Ackroyd (WA) was just 19 years old and a Lieutenant in the Royal Marines. He commanded a section of three landing craft of 807 LCV(P) Flotilla that went from Hayling Island to Gold Beach overnight on 5th-6th June 1944. Their load was jerrycans of fuel. Below is a link to his diary around the time of D-Day and a letter he wrote to his parents, shortly after the campaign began.

From a young age William Ackroyd kept a diary and this continued throughout most of his life. He favoured an appointment style diary. In the months leading up to D-Day the entries show that he was at Beaulieu (last entry is on 29 May when he was (OOD) Officer of the Day). Thereafter, he kept a diary of sorts in a small, loose-leaf notebook, held together by three treasury tags.

Below is a link to his diary around the time of D-Day and a letter he wrote to his parents, shortly after the campaign began.

Click here to read excerpts from the The Diary of William Ackroyd.

Monday 12 June

My dearest Mum and Dad,

I hope you got my little card alright, sorry there was so little news on it, but up till now I haven’t found very much time for writing. All round I have rarely felt better and am sure that French air is doing me good!The crossing was, apart from the nightly air raids, by far the most uncomfortable thing any of us have experienced yet. As they said on the wireless, the weather was pretty grim and believe me, it was.

(Tuesday – I was called away)

There were only about four of us who were not thoroughly ill – most of the fellows were so sick they didn’t know whether they were on the sea or on the top deck of a horse bus! I was the only one in my boat – even in my flotilla, who was not totally incapacitated, either lying on the deck or hanging head down with his head in the bilges! One of my fellow officers were so ill he wore out two pairs of socks, walking from the well to the gunwales to be sick over the side!!!

On the Monday night I and three other craft got separated from the rest of the flotilla and spent some five hours searching for them. Luckily, I knew where we were rendezvousing and picked them up about halfway across: there was a rattling gale blowing the whole time and waves varying from twelve to fourteen feet high throughout Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday. How our little craft stood up to it, I don’t know. You probably heard the little bit of praise we got on yesterday’s six o’clock news for crossing – I think we deserved it. I stepped on French soil on the evening of D + 1 but can’t say it gave me much of a thrill.

We are feeding very well now, but for the first two days it was biscuits and herrings in tomato sauce. On the way over. Godbelove (?), my opposite number, felt hungry and told his MOA1to open a tin of ‘herrings in’. After a period of half an hour or so, Alf wondered what had happened to him and when he had a look found the poor boy groaning on the deck with his head in the bilges -the task had been too much for him!!! I just missed seeing Winnie and Smuts on the beach yesterday, which was a pity – apparently he was in high spirits.

I’m looking foreward (sic) very much to a letter from you – the more you write, the better I shall feel.

At the moment, in odd patches of spare time, I am making a house flag for my boat it should be pretty tidly when finished. I’m hoping it will look something like this.This is supposed to be our crest.

Unfortunately I have run out of news so will end my very dearest love to you all.

from yr son Billy.

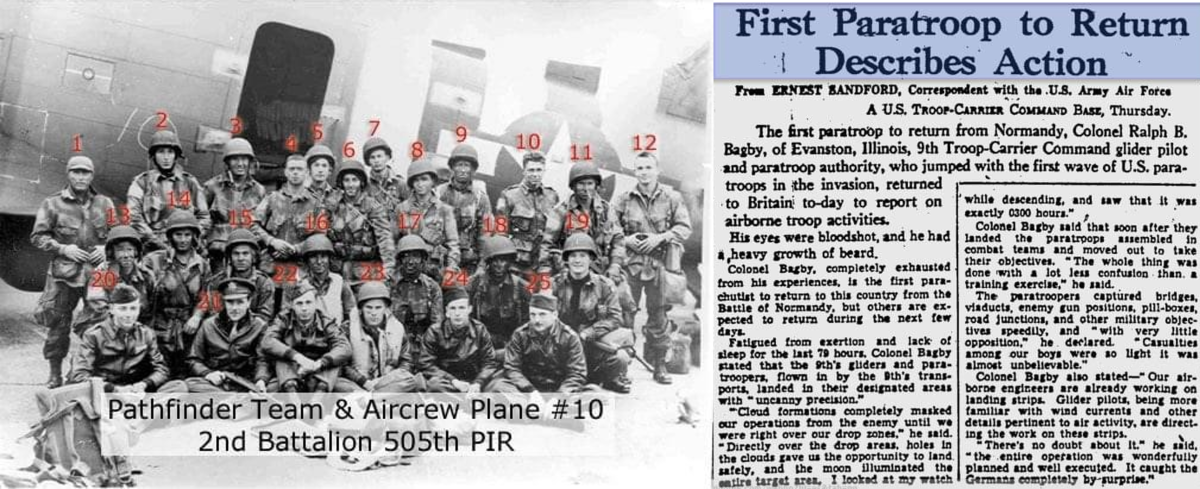

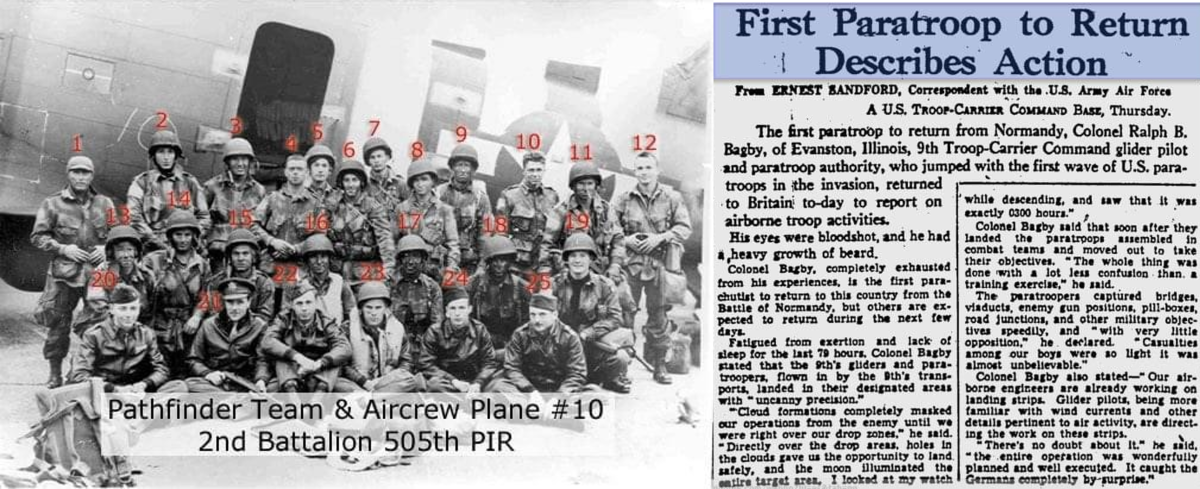

Colonel Ralph “Baz” Bagby

Samuel Dawson’s Uncle Ralph “Baz” Bagby was larger than life.

Ralph Bagby was an aerial observer in WWI. After the war, while still in Europe, he was trained as a fighter pilot. He became friends with such American aviation greats, as Doolittle and Spaatz. He took part in the Great American Air Race from New York to California and back in the 1920s. After meeting a girl in Washington, DC he decided the military life was not conducive to having a family so he became a civilian.

After the US entered WWII, Baz volunteered to serve. Doolittle wanted him to help with something secret (the Tokyo raid), but Baz was not in the best of shape. By the time he was medically cleared, the raid had taken place.

Baz was too old for fighters, so he was given a position in the transport command. During the invasion of Sicily, he was a wing commander and was nearly shot down by friendly forces.

For the invasion of Normandy, D-Day, Baz was moved to Eisenhower’s headquarters and worked on Operation Neptune, the airborne portion of D-Day. Baz was very concerned about a repetition of the Sicily fratricide and wanted to go with the first wave to make sure everything went well. He knew with his age Eisenhower would never approve. So Baz talked to the US 82nd Airborne Division commander, General Gavin, and convinced him to let him go with the first wave. Gavin thought Baz meant “go with the first wave” as in fly out and back.

The day before D-Day Baz went AWOL (Absent Without Leave) and went to the flight line. The 505th parachute infantry regiment pathfinder commander was told that an Army Air Corps colonel would be going with him. He thought that meant jumping with him. So when Baz showed up he was rigged for the jump and given the “short course” on jumping.

Baz didn’t correct the misunderstanding and made his first and only parachute jump, a night combat jump with the 505th PIR pathfinders on D-Day.

When General Eisenhower found out he was furious and wanted to court martial Baz.

But his exploits made the front pages so instead Baz was given a Silver Star and a letter of reprimand.

Click here to read the News Article from the Glasgow Herald, June 9, 1944.

Richard Jones, T/83391 RASC, 6th Airborne Paratroop Division

Richard A Jones explains what it was like for his father in Ranville at the time.

My father, Richard Jones, T/83391 RASC, was in the 6th Airborne Paratroop Division.

On the night of 5th June, my father was dropped with his regiment at Ranville. To his surprise he and another soldier came across a German soldier, who immediately surrendered to them and they handed him over to the officers. They then fought their way to Pegasus Bridge to meet up with the glider units who went in early on 6th June. They secured Pegasus Bridge and were there when Lord Lovat came across with his men and piper. My father was then ordered to drive Lord Lovat to Headquarters in a jeep. He was then in Caen which was still partly occupied by the German army. He then returned to his unit and shortly after was wounded when the jeep went over a landmine, he was thrown clear but the other soldiers, Canadians, were all killed. He was repatriated and recovered in hospital, spending the remainder of the war in Egypt.

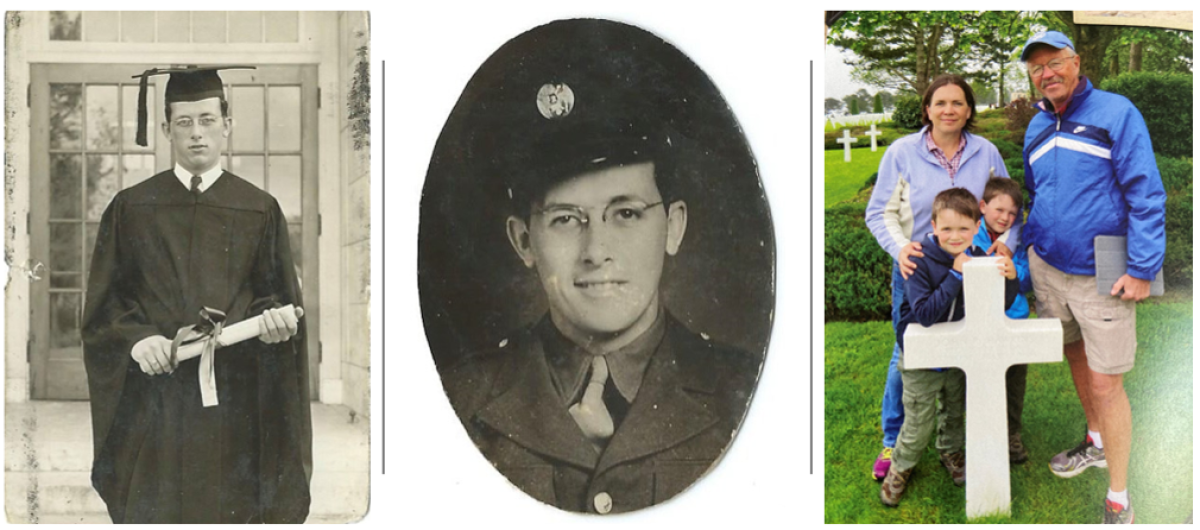

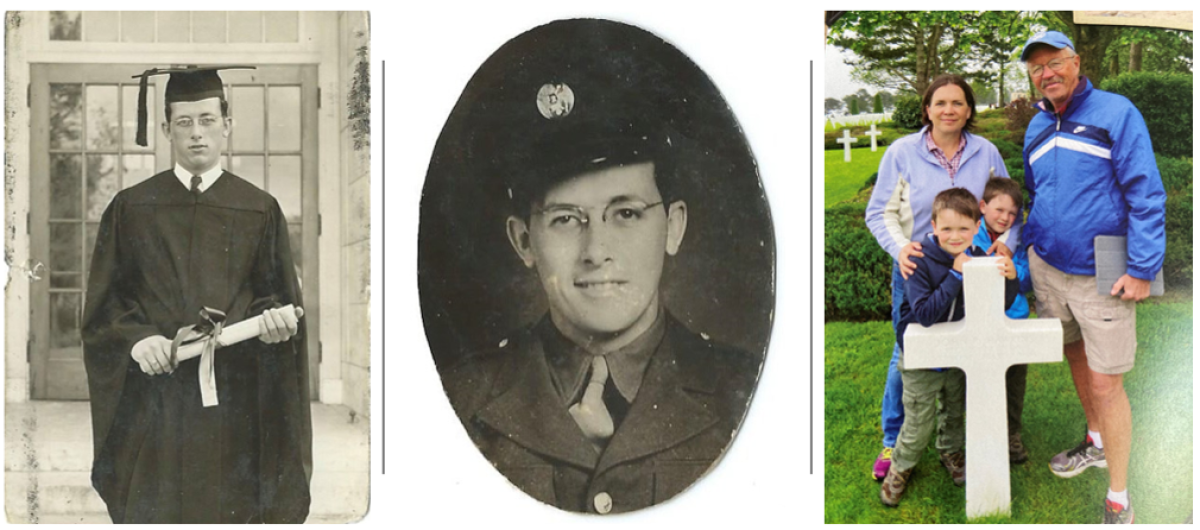

Private First Class Jack Hawkins (US Army), 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division.

Colleen Mitchell shares the story of her father’s cousin, who served in the U.S. Army during World War II.

John (aka Jack) R. Hawkins was first cousin to my dad, James Flannigan. He was born in 1923 and entered the service from Vermont. At the time of his death on 10th July 1944, he held the rank of Private First Class (U.S. Army) and was serving in the 39th Infantry Regiment, 9th Infantry Division. He was awarded the Purple Heart.My dad, James Flannigan, was born on D-Day, June 6th, 1944, in Albany, NY. Just one month later, his Big Cousin Jack passed away in France, serving our country and so many others.

When our family visited Jack at the Normandy American Cemetery at Omaha Beach, his permanent resting place, on a beautiful May day in 2015, our then 6 year old twin boys, Cole and Luke, told Papa that it was so nice that his cousin’s grave was right beside the chapel, under a lovely tree, with a view of the water. We are grateful that our family was finally able to visit Cousin Jack, at Plot H, Row 9, Grave 12.

Colleen Mitchell is an USAF Reservist Lt Col and her husband is a USAF Col assigned to Ramstein AB, Germany.

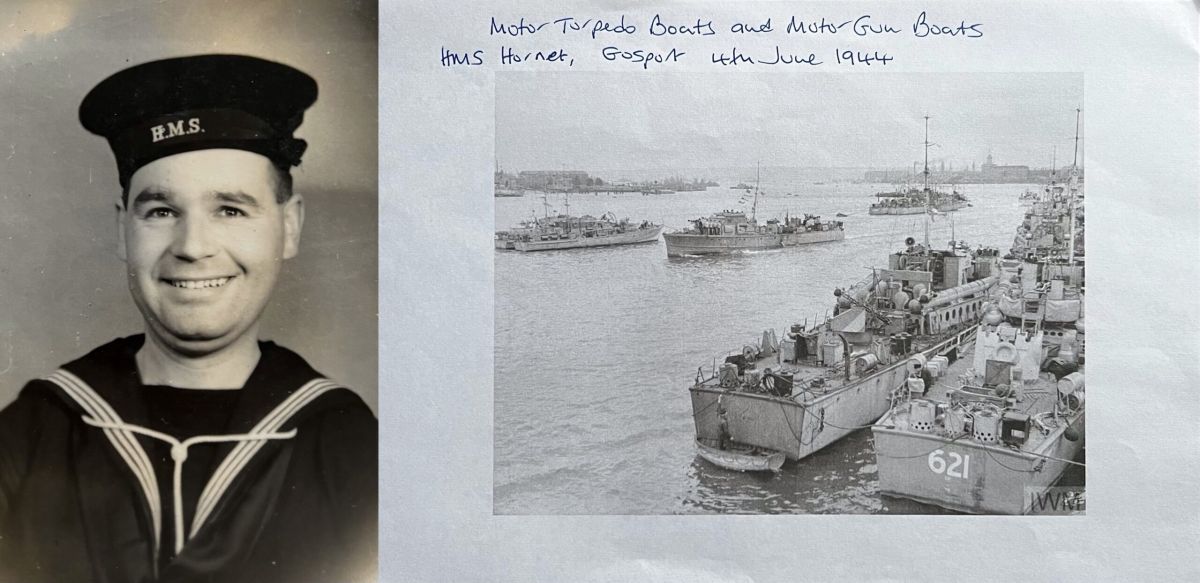

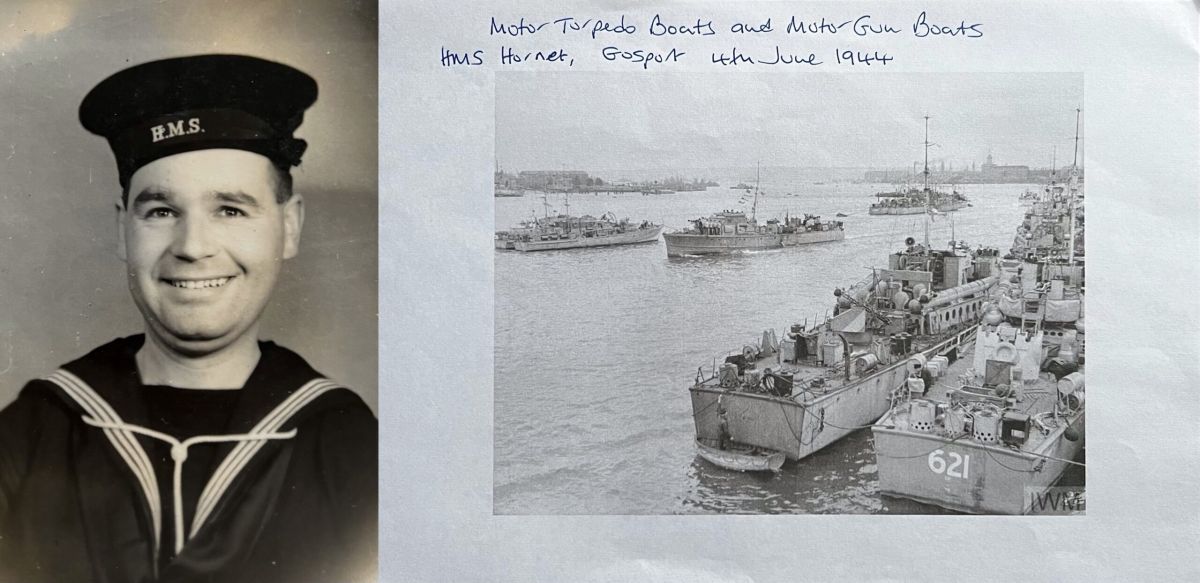

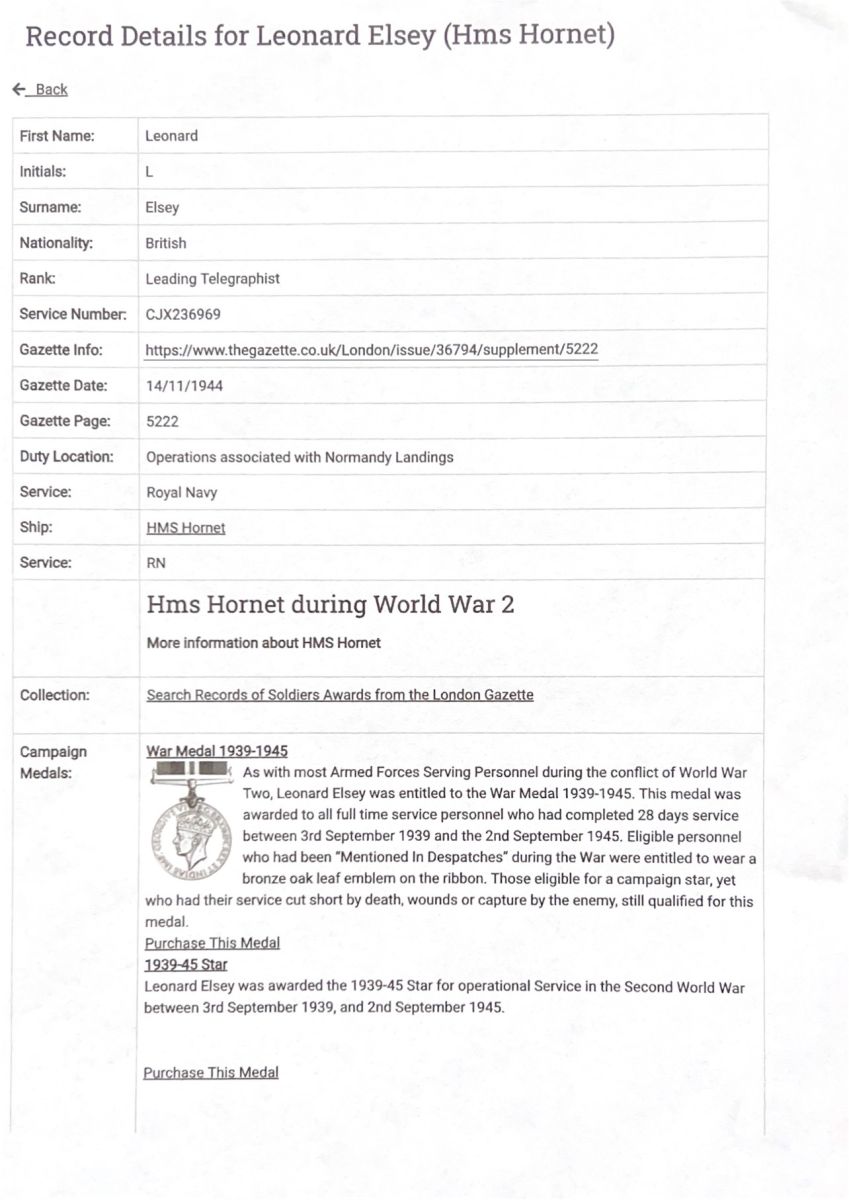

Leading Telegraphist Leonard Elsey, HMS Hornet

Above is a photo of Leonard Elsey in uniform, along with a photo of HMS Hornet, taken on 4th June 1944.

One of Michael Smith’s uncles, Leonard Elsey, served on Motor Guns Boats during WW2. He took part in operational duties asssociated with the Normandy Landings. Leonard was badly wounded at some stage during the war and was Mentioned in Despatches. He passed away in 1984.

Below are details of Leonard Elsey’s service record.

Leonard Elsey, HMS Hornet

Captain Leslie Coleman, Royal Engineers

Michael J Coleman’s father, Captain Leslie Coleman, Royal Engineers, was responsible for printing maps for the D-Day landings. Following D-Day, he then commanded a mobile printing unit following the frontline troops through Europe. Captain Coleman wrote a host of accounts from his military career, including his involvement with the ‘Home Guard’ before he enlisted; the fact that he wanted to join the cavalry, although he was a printer!; as well as his experience as the first non-frontline Officer into Belsen, to record the camp photographically. Here is a portion of his writings relating to the D-Day landings:

Dawn was breaking as we approached the distant shore and soon there was frantic activity to get everything ready for the “off”. Shackles removed and troops in their vehicles, the tension mounted as we waited for the moment. My company was to go off first and I was in the lead vehicle driven by my batman/drive, a short stocky Scot. My one concern was that if the water was deep enough to flood into the cab he might take his foot off the accelerator and stall the engine and in anticipation of his natural reflexes, I insisted he tie his food to the pedal.

At about 9am, the ships engines died and as the bow of the ship opened up, so did the engines of all the vehicles onboard. A defeaning row and fumes which almost obliterated the view. A signaller gave the OK and off we lumbered down the ramp and into the sea, striking out for the beach beyond. A beach on which I failed to recognise any of the salient landmarks I had expected to see for the simple reason, as quickly became apparent, that the tide had swept us up sideways and we were not landing where it had been intended. Here was I, heading a convoy landing on the Normandy beaches, beaches I had studied for months in minute detail, and I hadn’t a clue as to where I was. On my lap was a full scale map, but it told me nothing. Waterproofed in the rear of my vehicle were other maps covering every inch of the coast, but they could not be got at. We had arrived, but what a glorious shambles.

As we lumbered out of the sea and onto the shore, white tapes indicated the way off the beach and onto the road which ran behind some sandhills. Beach officers waved us on and to either side notices warned that either side of our narrow exit were mines. It was a case of the blind leading the blind, and all I could do was press on regardless and the remainder of my company were following behind. No doubt they and my driver had confidence that the “boss” knew where he was going. Little did they know.

We finally landed at about 10am – the sun was shining and the countryside was not unlike Devon or Cornwall, as we made our slow pace along the country road. There was no longer any sign of other vehicles, no sign of any people about and quite an enjoyable run in the country – except for the fact that we were lost. Where was everybody?

Suddenly, as we rounded a bend, other vehicles were coming towards us. They were the back end of my convoy and the surprise on their faces only equalled mine, but no way could either of us stop on this high hedged narrow road. We continued on our way and after further twists and turns arrived, quite by chance, at an open area crowded with tanks, troops and vehicles of all sorts, and as we pulled off the road, discovered to my profound relief that every one of my vehicles were neatly drawn up behind me. I did not ask them where the hell they had been, as they could well have asked me the same thing – for which I had no answer.

Whilst the drivers set about de-waterproofing the vehicles, I de-waterproofed our maps of the area to discover that our two hour midday jaunt of Normandy, in the glorious summer sunshine, has taken us well into enemy territory, but luckily along byroads, a stone’s throw away from where our troops, and theirs, were in contact… Hence, the absence of anyone or anything. It was our good fortune that our vehicles only proceeded at snails pace, as had we been travelling faster and farther, we must surely have managed to get ourselves captured before the show had properly started. This was only the first occasion where ‘Ignorance was Bliss and it would have been Folly to be Wise.’ Fortunately, my company showed no sign of appreciating the danger I had put them in and I was certainly not going to enlighten them. They retained their confidence in the “boss”, knowing what he was doing and I vowed that it was a good omen that we were destined to survive, whatever happened.

Sergeant Hugh Stanton, 4th County of London Yeomanry Regiment

Image Credit: Photograph by Major Wilfred Herbert James Sale, MC, 3rd/4th County of London Yeomanry (Sharpshooters), World War Two, North West Europe, 1945 (c).

Stanton and Pace’s regiment, 3rd/4th County of London Yeomanry (Sharpshooters) was formed in July 1944 following the amalgamation of two existing Sharpshooters’ regiments, 3rd and 4th County of London Yeomanry. Both had suffered heavy losses in Normandy. The new composite regiment fought its way across North West Europe with Brigadier Mike Carver’s 4th Armoured Brigade.

Paul Stanton shares his father Sergeant Hugh Stanton’s story. My father was:

Name: Sgt Hugh Stanton

Enlisted: April 1939, age 18

Regiment: ‘A’ Sqn, 4th County of London Yeomanry Regiment

(subsequently 3/4th County of London Yeomanry on amalgamation of Regiments)

7 Armored Division (Desert Rats)

Equipment: Commander, Cromwell Tank

Served: Africa, Italy, Europe

Awarded US Silver Star for actions in Europe

The text below is transcribed from notes written by Hugh, and covers the unit landing on Gold Beach on 6 June 1944 and subsequent action.

‘…Landed broadside on to the beach, had to make a left turn to climb ashore. Last tank off the LCT so had quite a drop. Was very glad to get off as was sea-sick. Assembled inland a mile or so north of Bayeux shedding waterproofing on the way and stayed the night. Snipers active but that was all. Field was waist high in corn and only the turrets of tanks were visible. Moved off the next morning through Bayeux little cobbled streets, just wide enough for a tank. I only had a 200 ‘thou map to work on which was hopeless. We pulled off left main and did protection left. Shelling started and one tank was hit on turret and commander killed. Saw it was from 8th Brigade on our left flank. Showed smoke signals etc. but they continued to shell us for an hour or so. We were held up by a small impassable river, only way over was by the road. ‘C’ or ‘D’ had contacted the enemy on the right flank.

We tried to take the village of Buceels but were held out. Mitford Cotton was sniped through the neck and was evacuated. It was getting dark and my troop, with the assistance of some infantry, Gloucesters, wearing a Sphinx, were to attack the village and take it. I was leading tank and overtook Jimmy Lamb who warned me of an 88 down the road. Had to advance, keeping level with the leading infantryman. I had one infantryman on the back of my tank to point out targets. Everyone went in firing everything they could. A German threw a grenade which exploded on the track and another sniped at me from an upstairs window. By this time the whole village was ablaze and infantry were hosing the houses with Brens etc…’

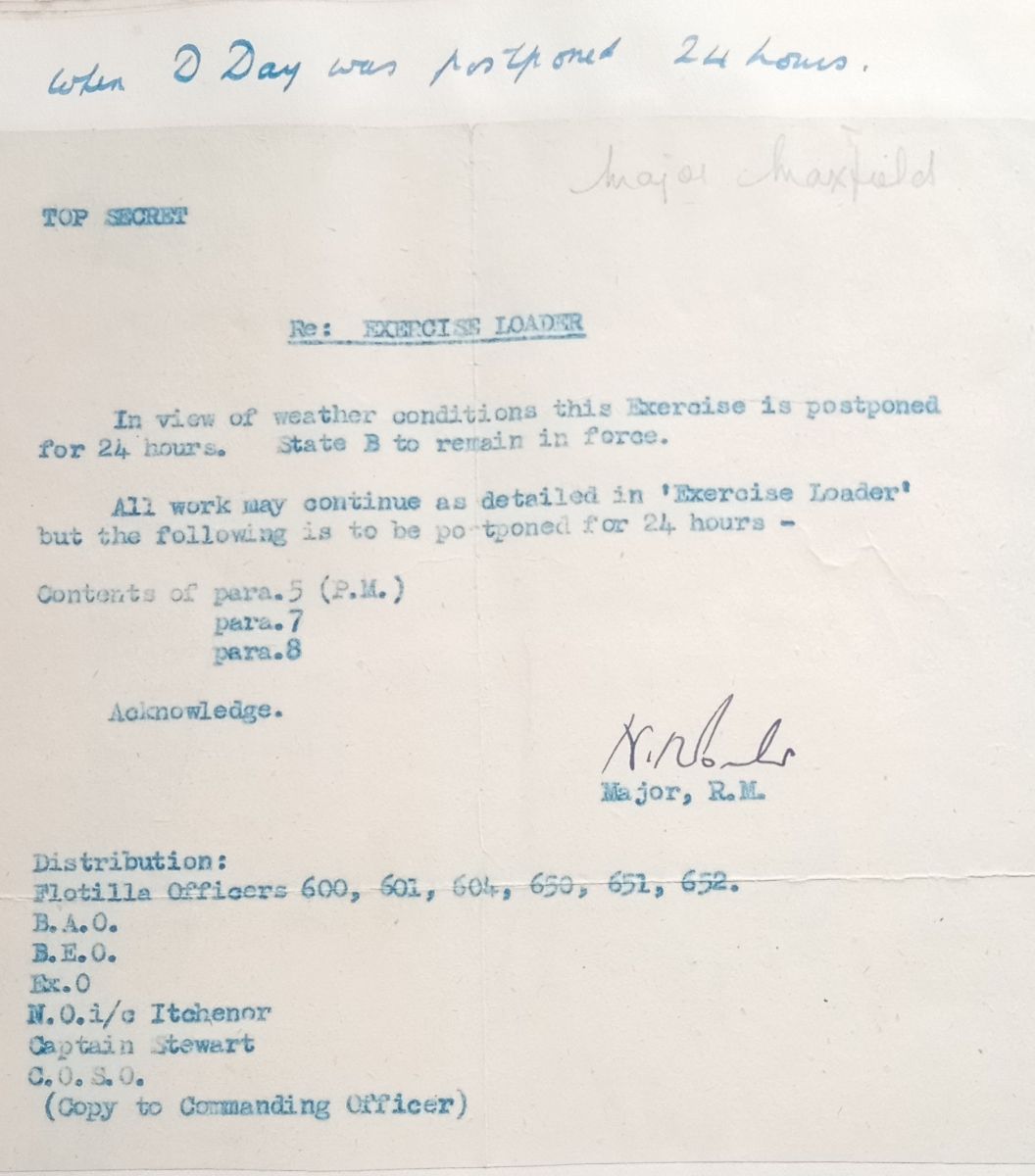

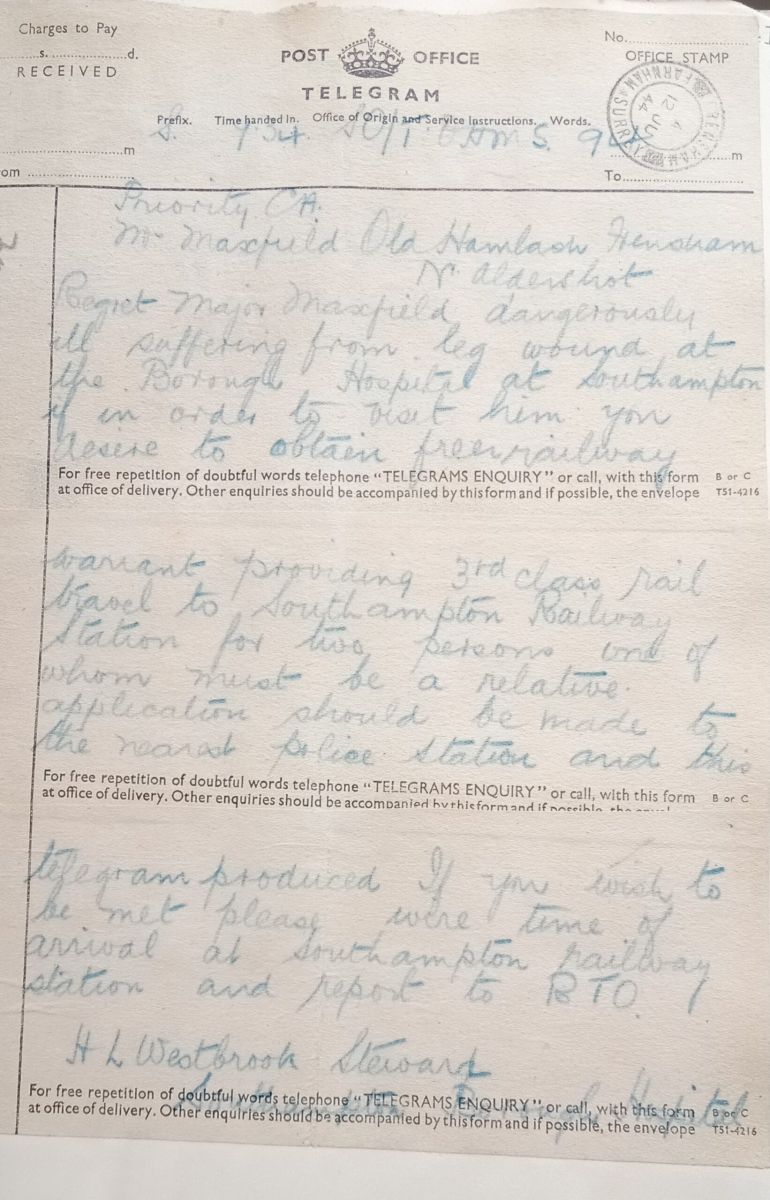

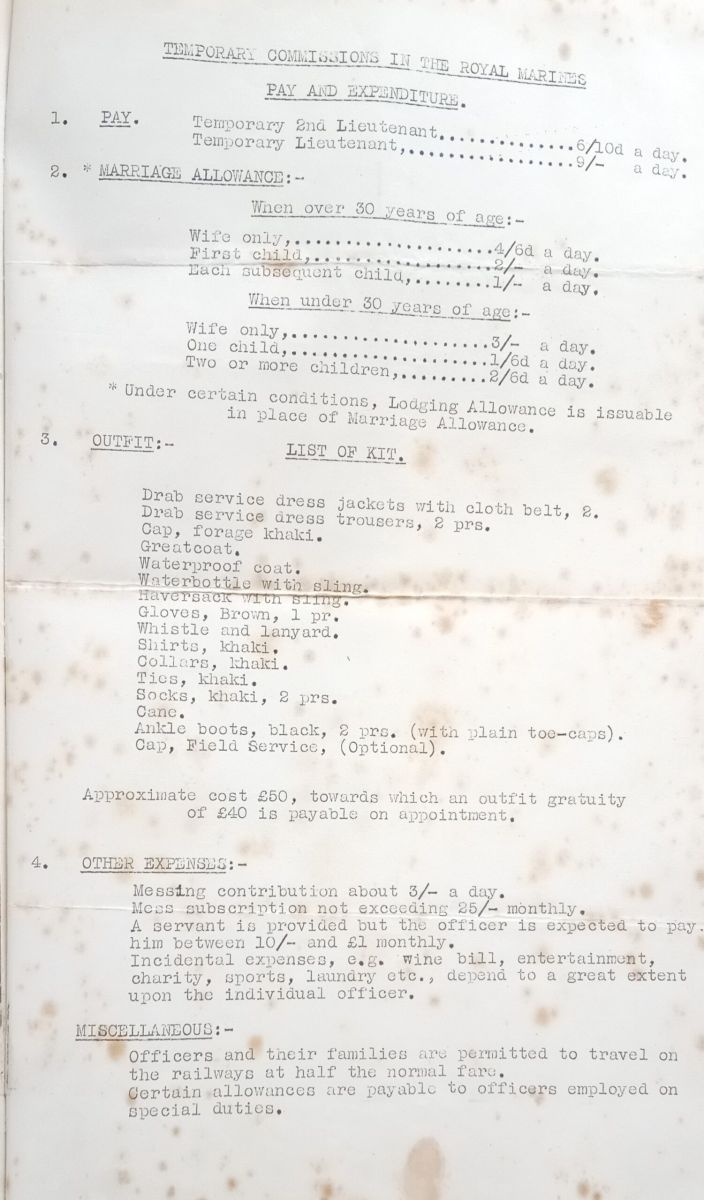

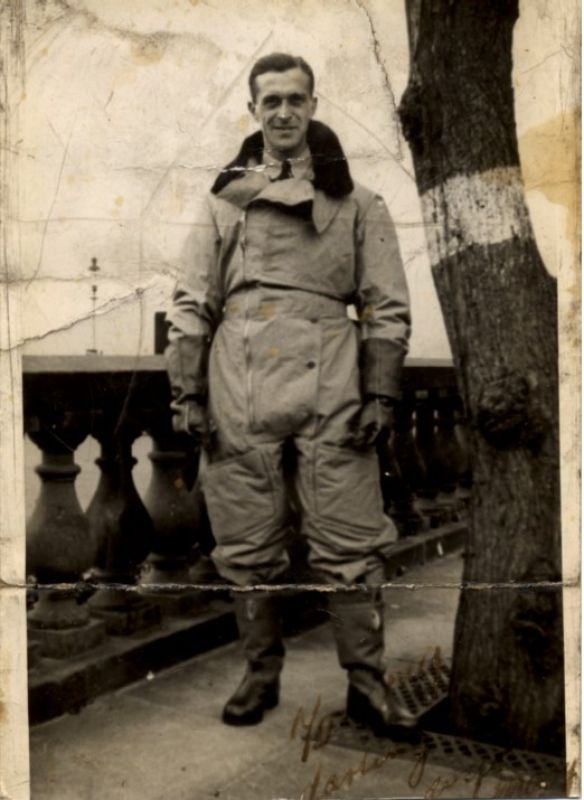

Major John Farquhar Maxfield, Royal Marines

Photos above include: Top Secret message that D-Day was postponed | 12th June Telegram informing Major Maxfield’s family of his injuries and arrangements for visiting him at hospital in Southampton | Details of Pay & Expenditure Allowances for Temporary Commissions in the Royal Marines

Fr Stephen Maxfield recounts his father’s part in D-Day.

In 1943, my father was stationed in Ceylon being the commanding officer of an outfit called B.D.O.1. This was a Royal Marine battery, mostly I think concerned with AA guns. I remember that he was very pleased with himself, as they had managed to shoot down a Japanese fighter. He reckoned this was a fluke, as he had a very low opinion of our AA guns.

My father was recalled to England travelling on the Queen Mary, which did not have to go in a convoy, as she could out-run all German U-boats. He was recalled to help with planning the Normandy landings. He was based with the staff at Southwick. He said that he was in charge of an outfit called the “Naval Advanced Guard”. The task was to act as a liaison between the naval warship’s guns and the army on the ground. (I assume that a lot of the planning involved assessing intelligence about German positions and working out ranges etc for the naval artillery). He was one of the people who received the Top Secret message that D-Day was postponed. See above.

My recollection is that he was not in a landing craft, but some other vessel. This went off course and he saw the carnage on Omaha beach from a distance. They then left and he was landed on the correct beach, which I assume must have been Gold Beach. He did not have much to say about what happened next except they took over a German HQ of some kind, where they found portraits of Hitler and a large quantity of pink Champagne. He mentioned a lot of evil smelling dead cows!

On D-Day+ 3 (I think) my father was driving a Jeep with three other passengers, when they took a wrong turning and he reversed into a farm entrance which was mined with a British bomb captured at Dunkirk. This blew up the jeep tearing off one of father’s legs, badly damaging the other and filling much of his body with shrapnel. He was unconscious for four days and arrived in a hospital in Basingstoke. He was hospitalised for four years off and on until a very clever surgeon, found my father in bed waiting for a tin leg to be fitted at Roehampton. Seeing his other leg in plaster he asked: “What is wrong with that leg?” when being told that it was smashed below the knee and which surgeon he was under he was told “That is hopeless, that surgeon is a plumber. Tell the sister that your leg hurts next time she is making her rounds and I will have a look at it”. He did, and the surgeon screwed some pieces of bone from elsewhere in his leg to the fragments and saved the leg, albeit he was 5” shorter than he had been. The authorities evidently never reckoned this graft would hold as he was registered as 100% disabled.

Given the pain my father was sometimes in, and the phantom limb pain he had, which he described as like walking on barbed wire, my father was a remarkably well put together man. Yes, sometimes he was a bit sorry for himself and occasionally, a bit angry at the hand he had been dealt, but he remained cheerful. He was never in a wheel chair, though later on he found gin the best anaesthetic. Particularly real Pink Gin made with Angostura bitters in the Navy fashion!

There is one irony to end the story. When sitting down my father’s tin leg opened at the knee. One morning when he was dressing, I (aged 4) poked my finger into the opening as he stood up, severing the end of my finger. I was rushed to the doctor where it was re-attached, and I have the scar to this day. I reckon this as a secondary war wound!

Flying Officer Max Godden, RAF 297 Squadron

Roger Brickell shares the story of his father-in-law’s part in D-Day.

My father-in-law (Flying Officer Max Godden) was a pilot in RAF 297 Squadron, flying Albermales. Max had been with 297 since it was formed as the experimental squadron for the airborne forces.

I was interested to read the piece about Flight Sergeant Eric Escott – the navigator whose aircraft took off before midnight on 5th June. My father-in-law was pilot of the third aircraft behind his. Max had to make two runs over the DZ as the door would not open for the Pathfinders to jump on the first pass. His navigator was “Dusty” Miller, so [these two – Eric Escott and “Dusty” Miller] might have been known to each other. We did meet “Dusty” Miller after Max died, as he kept in touch with his crew.

Later on 6th June, they were the first aircraft off towing a Hoisa glider on Operation Mallard returning safely. His glider pilot was Captain Neale, who sadly died at Arnham. Max did not fly him in as he was taken off ops three days before it took place.

Like many others, Max hardly spoke about the war and became a Priest.

The Father of Lt Col Jim Bexfield (Ret’d)

The father of Lt Col Jim Bexfield’s (Ret’d) flew a B-17 on D-Day. He said it was his easiest mission – short, low altitude, and no flak from German guns. It is the only mission he flew with his dog as a passenger. Flight Officer Norman Bradford,

D-Day on the Home Front

Sally Smith MBE explains what was like for her parents in England at the time.

My mother and father were both University Lecturers at Kings College London during the war. For much of the war the college had been evacuated to Bristol, sharing facilities with that University…. Not to much good as Bristol was badly bombed too. But in spring 1944, Kings College moved back to London, just in time for the V1’s arrival.

On 6th June, my father, along with other colleagues, was fire watching on the roof. My mother, Dr Lilian Cronne, was invidulating finals exams for the mainly women students in the history department. They had been given the option of not sitting the exams because of the danger of being in a room with a glass domed roof, but I understand only one student under pressure from her parents did this.

During the morning, another staff member came in carrying the first edition of the London Evening Standard, carrying the headline news of the Normandy Invasion. Obviously nothing could be said, as silence had to prevail. So my mother walk between the silent rows holding up the front page. Not a word was spoken, but she said the excitement was palpable and she sensed a renewed vigour and determination amongst the students as the finished their papers.

During the war my mother had been offered a job as a spy mistress to recruit women for the SOE as she was trilingual English, French and German. She had decided to stick with her academic wartime contract. She felt that sending young women to a possible death was not something she had the strength to do. The reason being that she herself was the daughter of German parents, and knew she was on a death list had the UK been invaded. She eventually lived to be 101.

Captain W R Canning RN remembers D-Day, as a 13-year old boy at school in Somerset

In 1944, I was a thirteen year old boarder at Durlston Court Prep School for boys in Somerset. The school had been evacuated from Swanage in 1944 to a large family estate, Earnshill House, surrounded by the Somerset Levels, near the village of Hambridge. This vast flat area housed a number of wartime airfields, including a huge one that accommodated a large number of US Air Force Dakotas and Horsa gliders. What is more, the airfield was within walking distance from where the school was now billetted – manna from heaven for a bunch of boys, who had a keen interest in all things military – and we were frequent visitors to the totally unfenced edge of the airfield, from which there was incessant activity.

In the early hours of 6th June 1944 (and with no prior warning of course), my dormitory of senior boys was woken by the incessant roar of aircraft taking off from the airfield, and even at that age, we immediately concluded that the long awaited Allied invasion of Normandy, had begun. Our ‘dorm’ on the ground floor had access (after a little manipulation of the lock) to a lawn and we piled out in an attempt to catch a glimpse of this significant event, but it was still dark and we heard more than we could see. Nevertheless, it was exciting stuff and we mad ethe most if it, until eventually being ordered back inside.

Jeremy Brade recalls his father’s boyhood memories of life in rural Hampshire

My father was born in 1933 and grew up in rural Hampshire. He told us that in late May, his village was surrounded by “endless military vehicles parked in the lanes and fields”. The great number of troops assembled with the vehicles was Canadian. As a boy of 11, he and his friend spent days watching and visiting them. One morning, he woke up – it must have been 3 or 4 June – and they had all disappeared.

Mark Fitall’s father, as a boy of 11 years, remembers D-Day

My recently deceased father’s family lived in Eastleigh, Hampshire, and his lasting memory was of the sky being literally black with aircraft.

Margaret Fryer’s mother worked as a nurse

My late mother, Daphne Helsby nee Whittle, was nursing at the time, I believe at the Royal Alexandra Hospital in Portsmouth. She remembered many D-Day casualties being brought in. All had their medical details scribbled on the dressings, including whether or not they had received penicillin, a rare and precious commodity then.

D-Day Poem by Leslie D. Knights

Duncan Knights’ father, Leslie Knights, contracted polio as a child which left him severely disabled. He was consequently unable to serve during the Second World War (a source of continued frustration, as his son remembers) apart from a year or two in the Home Guard. With reduced mobility, he would in all probability, have been limited to administrative duties. Leslie was always incredibly proud of the achievements of his contemporaries in the regular forces and he expressed this in some of the poetry he wrote throughout his life.

This poem “Canaan” was composed fairly soon after D-Day, as an early draft was written on the back of an old letter from August 1943.

CANAAN (6TH JUNE 1944)

by Leslie D. Knights

That was, O Britain, a proud day for thee

As thy armadas sailed by sea and air;

And men, who knew the bitterness of bare

Sands under fire at Dunkirk, lived to see

Thy strength and valour move in majesty:

While spirits of dead heroes, who could dare

Torture and death for secret war, did share

In their compatriots’ guerdon – ‘ Liberty! ‘

But, now the beach-head has been stormed and won

And horrors of the battle in fresh earth

Turned by the plough lie sweet for evermore,

Do not, fair Britain, dream in noonday sun;

Nor wail the dead, yet loose the prize of worth

For which they toiled to save here on our shore.

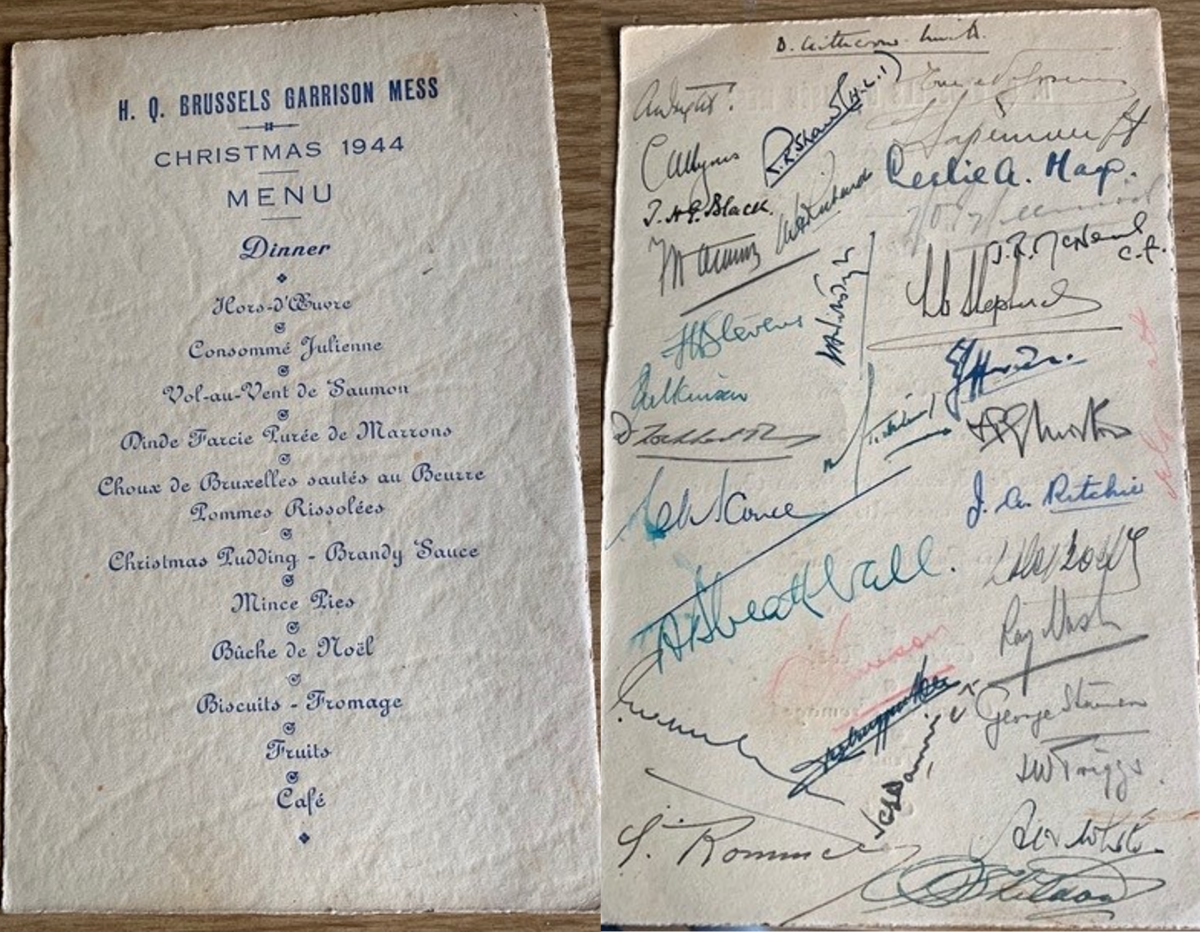

c.1944 Documents of Interest

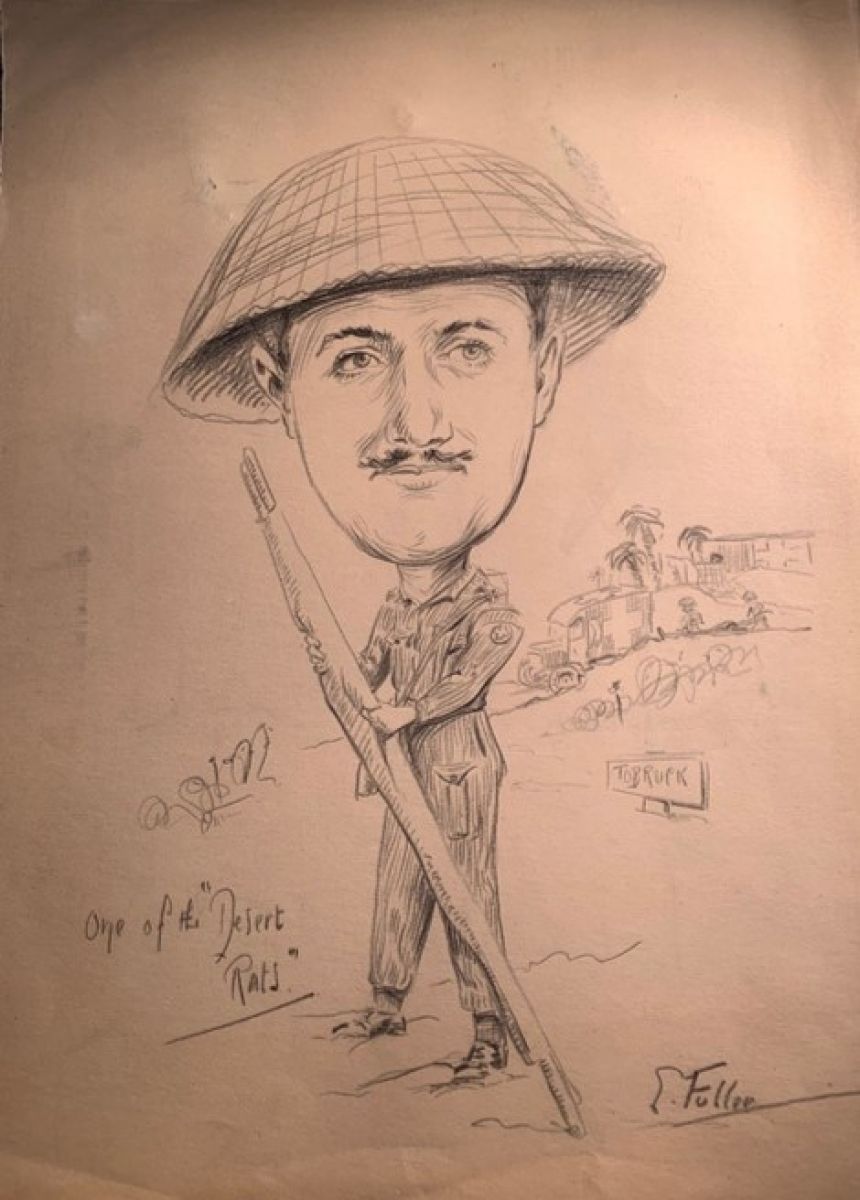

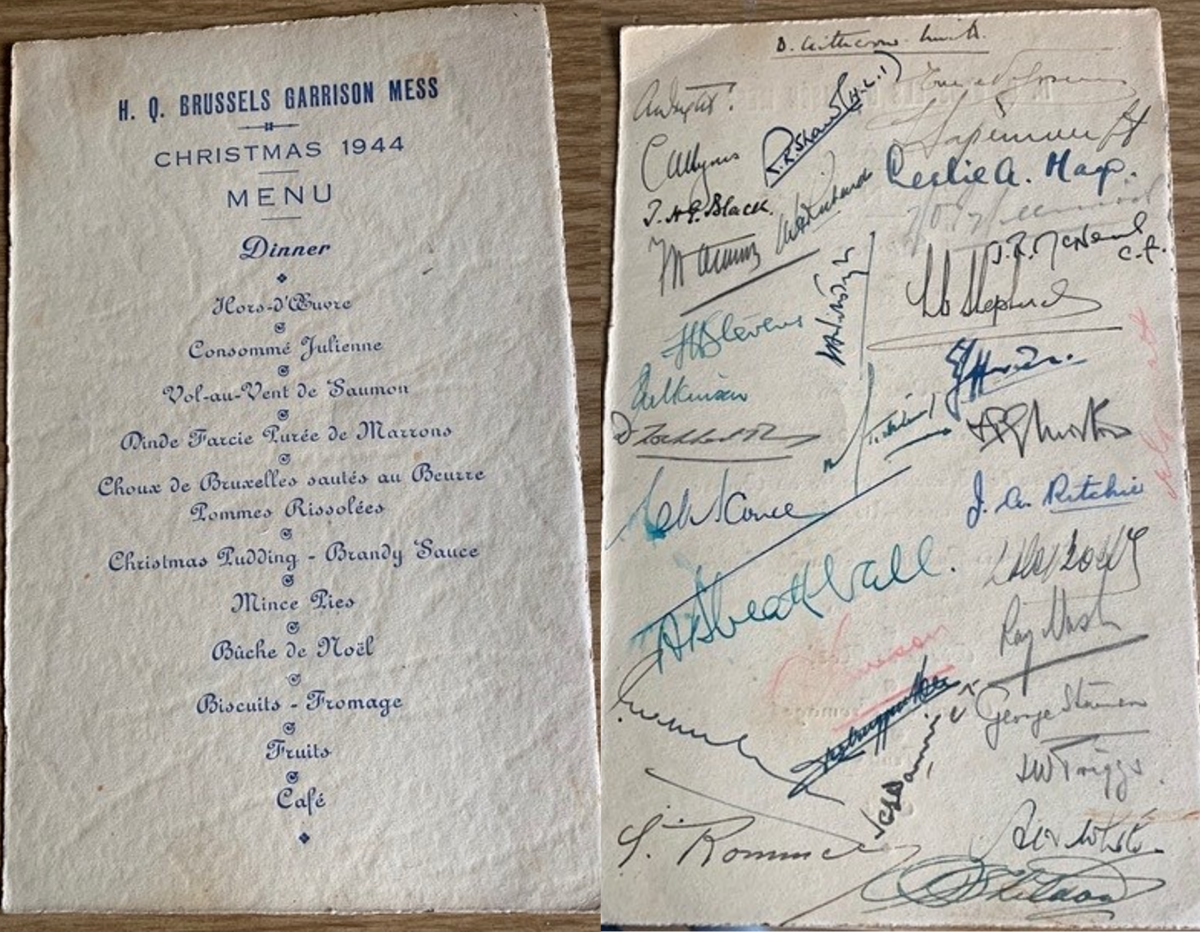

Photo above: The Christmas 1944 Menu from the H.Q. Brussels Garrison Mess at the Plaza Hotel in Brussels. Photo below: The sketch by a glorious soldier, given to the aunt of Jacques De Backer, (who shared both images).